The Plot, Volume 2

From Wikousta

| Revision as of 04:53, 15 June 2020 (edit) Im17yy (Talk | contribs) (→'''Group 8 – The Plot, Volume 2''') ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 05:08, 15 June 2020 (edit) (undo) Im17yy (Talk | contribs) (→Works Cited) Next diff → |

||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

| == Works Cited == | == Works Cited == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Fort Shelby/Fort Detroit''. ''Military History of the Upper Great Lakes'', https://ss.sites.mtu.edu/mhugl/2015/10/11/fort-shelbyfort-detroit/. Accessed 14 June 2020. | ||

| McCrea, Harold. ''Wacousta or, The Prophecy: A Tale of the Canadas.'' 1987. ''Goodreads,'' | McCrea, Harold. ''Wacousta or, The Prophecy: A Tale of the Canadas.'' 1987. ''Goodreads,'' | ||

Revision as of 05:08, 15 June 2020

Contents |

Group 8 – The Plot, Volume 2

Map out the plot of each chapter in Volume 2 by highlighting the key events that transpire, the key themes that appear, and the significant changes in circumstances. Provide an overview of the importance of this volume to the work as a whole.

Overview for Volume Two

Chapter 1

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 2

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 3

Key Events

Back at the fort, “the garrison were once more summoned to arms (...) A body of Indians they had traced and lost at intervals (...) were at length developing themselves in force near the bombproof. With a readiness which long experience and watchfulness had rendered in some degree habitual to the English soldiers, the troops flew to their respective posts” (183). The Indians come without war paint “nor were their arms of a description to carry intimidation to a disciplined and fortified soldiery” (183). Several of the English leaders were collected within the elevated bomb-proof, holding a short but important conference apart from their men. The men converse about a previous encounter with Ponteac, the Ottawa chief. An artilleryman shouts from his station that the Indians are preparing to show a white flag, “a truce in all its bearings” (185). Captain Erskine remarks on how Ponteac has acquired lessons since their previous encounter. The garrison is suspicious of this action, unsure as to how the Indians recognized this symbolization of peace, it seems to be of European nature, a civilized method. Captain Wentworth finds relief in their counter-plot to oppose a sudden attack. The large French flag is drawn.

The governor greets the Indians and engages in conversation with Ponteac. The Indians come in search for peace and to bury the war hatchet that has been stricken. The garrison questions the true intentions of peace, while Ponteac expresses the shame in the blood drawn over their feud. The governor accepts this proposal, however, peace can only be made in the council room, and “the great chief has a wampum belt on his shoulder and a calumet in his hand. His warriors, too, at his side” (189). The chief worries of the mediated treachery upon entry to the fort.

They prepare to enter the fort, throwing themselves into the hands of the Saganaw. The governor expresses that within the walls of peace, the Saganaw is ever open to them, but when the Indian warriors press it with the tomahawk in their hands, the big thunder is roused to anger. Captain Blessington is ordered to take vigilant caution, although no harm should be brought against the fort with their chief in their possession. “The noble-looking Ponteac trod the yielding planks that might in the next moment cut him off from his people forever. The other chiefs, following the example of their leader, evinced the same easy fearlessness of demeanour, nor glanced once behind them to see if there was anything to justify the apprehension of hidden danger” (192). As they advanced into the square, they looked around, expecting to behold the full array of their enemies; but, to their astonishment, not a soldier was to be seen. The chief meets the gaze of the governor.

Themes

This chapter relates to themes of contact and nation-building. As this novel as a whole navigates Settler and Indigenous relationships, this chapter in particular is a moment where we see the British and the Natives come together to evolve their complex and fragmented relationship. In past chapters, we have been dealing with violent encounters between bodies, but this section conveys as a shift, an effort to bury the war hatchet that has been stricken.

Chapter 4

Key Events

The Indians enter the council room and take "their seats upon the matting in the order prescribed by their rank among the tribes” (195), and proceeded to fill the pipe of peace. The governor and the Ottawa chief engage in conversation of the deceit and trickery used by both the Ottawa tribes and the Sanagaw upon the peacemaking ceremony. Both parties are rehashing history that formed this distrustful relationship that currently stands. They have diverging perceptions of past encounters, including the initiation of violence, betrayal, and fractured friendships.

The governor tauntingly questions the absence of the great pale warrior, who we know to be Wacosuta, to cause an upset among the Indians. The Ottawa chief accounts for his absence, as his voice can not speak, and he begins to accuse the Saganaw of sending spies to invade Indian territory. He shares the story of finding Onondato whose throat the spies of the Saganaw had cut, found upon near death on the bridge consequent to hearing a war call. Frequent glances, “expressive of their deep interest in the announcement of this word, passed between the governor and his officers” (201), as they made the connection to their two dispatched soldiers. The Ottawa chief remarks that the warrior of the pale face, and the friend of the Ottawa chief, is sick, but not dead. “He lies without motion in his tent, and his voice cannot speak to his friend to tell him who were his enemies, that he may bring their scalps to hang up within his wigwam. But the pale warrior will soon be well, and his arm will be stronger than ever to spill the blood of the Saganaw as he has done before” (202).

The governor questions the intentions of this ceremony, as it is one of peace, but such violence and revenge are alluded to in future contact. The Ottawa chief responded that the Ottawa and the Saganaw have not yet smoked together. When they have, the hatchet will be buried forever. “Until then, they are still enemies” (202).

“The Ottawa passed the pipe of ceremony, with which he was provided, to the governor. The latter put it to his lips, and commenced smoking. The Indians keenly, and half furtively, watched the act; and looks of deep intelligence, that escaped not the notice of the equally anxious and observant officers, passed among them” (204). The governor observes the pipe, and all its “ornaments are red like blood: it is the pipe of war, and not the pipe of peace” (204). He demands the Ottawa must come again. The Ottawa agrees, and there was “nothing to indicate the slightest doubt of their sincerity” (205). The Ottawa chief expresses his embarrassment, and claims that upon their next gathering, they will come with no armor, clothing, or weapons, they will be accompanied by their women and children, to show the Sangaw full trust and entry without fear.

The governor requests the presence of the pale warrior, to join in the peacemaking ceremony, to which the chief responds with hesitation, for the pale warrior is extremely ill, but should the Great Spirits accelerate his recovery, the governor’s request will be granted.

Ponteac suggests they gather again in three days time, when the governor responds that this is too soon, for the Sanagaw needs time to collect their presents, and the pale warrior needs time to recover. They agree to make peace in six days time. “The whole body again moved off in the direction of their encampment” (207).

Themes

This chapter prominently features themes of trickery motivated by cultural gain. The British see through the Ottawas kind of treachery by presenting a “pipe of war, and not the pipe of peace” (204), and counter trickery of their own. What appears to be an honest attempt of friendship and a “truce in all its bearings” (185), really proves to be ill-intentioned. When the chiefs trickery was spoiled, the initial attempt still allowed the Ottawa to infiltrate the fort and gather the information that will prepare them for their next gathering, and mislead the British in assuring them that no arms will accompany them, in hopes that perhaps the fort would disassemble their men. In this section, disguise can be seen in a metaphorical sense in that the chief is hiding his true intentions for the ceremony because he comes bearing the pipe of war. The Indigenous warriors on accounts of Wacousta want revenge for the land colonized by the British, but also want to assert their presence and defend the land and nature of their ancestral roots. They devise plans involving trickery to bring them closer to these desires. The fort foils these plans with the trickery of their own, downplaying their intelligence on the matter to secure their power status.

Chapter 5

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 6

Key Events

Chapter six begins with a white flag being raised by the Indians upon arrival to the bomb-proof. “On this occasion, they were without arms, offensive or defensive of any kind” (219). Between the unity of nations of the Ottawas, Delawares, and the Shawanees, these warriors might have been five-hundred in number. “Their bodies, necks, and arms were, with the exceptions of a few slight ornaments, entirely naked” (219). Each individual was presented with a stout sampling as an offering of peace and mutual cooperation. Accompanying the Indian warriors were an equal number of squaws. Thrown around their person was blankets, and “there was an air of constraint in their movements, which accorded ill with an occasion of festivity for which they were assembled” (220).

When it had been made known to the governor that the Indians come bearing no identifiable weaponry or defence, the soldiers were dismissed from their respective companies to the ramparts, now collected together in careless groups. This gestural disassembly was acknowledged “by the Indians by marks of approbation” (221).

The lack of soldiery in the is fort satisfactory, and “Ponteac, in particular, expressed the deepest exultation”(222). He fell behind his tribe, taking up the rear when he falls and meets the Earth. Ponteac signalled his safety. Upon entrance to the theatre of conference, the Indian chiefs noticed how the theatre seems enlarged with the absence of soldiers.

After greeting and engaging in conversation with the governor, the Ottawa chief “commenced filling the pipe of peace, correct on the present occasion with all its ornaments” (224). The absence of the pale warrior is acknowledged, he is still unwell and unable to join the ceremony, though his tongue is “full of wisdom” (224) but without speech.

Suddenly, “a wild, shrill cry from without the fort rang on the ears of the assembled council” (224), one to which all recognized as a signal of war. At this cry, the Indians tomahawks were brandished wildly over their heads and Ponteac bounded a pace forward to reach the governor with the deadly weapon, when, “at the sudden stamping of the foot of the latter upon the floor (...) twenty soldiers met the startled gaze of the astonished Indians” (225). Ponteac was astonished in the presence of prepared soldiers. This assured him of the dangers of their treachery that awaited him and his people. The once seemingly naked fort was flooded with hostile preparation. The Indians were “paralyzed in their movements by the unlooked-for display of a resisting force, threatening instant annihilation to those who should attempt to advance or to recede” (226). “The fall of Ponteac had been the effect of the design; and the yell pealed forth by him, on recovering his feet, as if in taunting reply to the laugh of his comrades, was in reality a signal intended for the guidance of the Indians without.” (227), The women and girls too were prepared, as they pulled back their dress and each had a tomahawk and short gun.

The governor orders for his soldiers to stand firm, but on high alert. "The pale face, the friend of the great chief of the Ottawas"(232) swiftly throws his tomahawk at the first impulse of his heart at Colonel De Haldimar, but changes his course as he redirects his aim. He wants revenge, and will not be robbed of the satisfaction as his own death would follow. The governor claims that “the Sanagaw is not a fool, and he can read the thoughts of his enemies upon their faces, and long before their lips have spoken” (231). “The Saganaw knew that they carried deceit in their hearts, and that they never meant to smoke the pipe of peace, or to bury the hatchet in the ground” (232). The governor claims that the Sanagaw does not betray their promises, which is why he will let them live, and go in peace, for he wishes to show the Ottawa the desire of the Sanagaw is to be friendly with Indians, and not to harm them. However, Ponteac claims that “the Ottawa is not a fool to believe the Sanagaw can sleep without revenge” (232). The fort disassembles, and the Indians immerse “once more into the heart of the forest (...) , the gate of the fort again firmly secured” (233).

Themes

The concept of the garrison mentality is evidenced in this chapter. Despite the promises between the garrison and the Natives to pursue peaceful relations, and although the Indians assured their visit would be made in full trust of the fort, the garrison still distrusted the forest and the wilderness of Native terrain. The fort was still densely armed with its soldiers and fatal weapons, prepared for “instant annihilation” (226), “which accorded ill with an occasion of festivity of peace for which they were assembled” (220). This prepared soldiery embodies the deeply rooted fear and distrust of the wilderness and its people, creating the panicked-driven soldiery of officers in the fort. The British consider the wilderness to be dangerous because of the unknown nature of the ‘wild’ humans who are one with the land, an unexplored and foreign space. The wilderness, and the sense of danger that pervades it, helps to justify the civilizing force and prepared soldiery of the garrison. Confronted with the novelty of this new world they invaded, they anticipate deceit and danger in every shadow.

Examples of disguise, misrecognition, and deception used in this chapter, including the seemingly naked bodies of the Indians, their civilized and unarmed approaches, and the discharged British soldiers, speaks to a breakdown and distrust in visual cues. Nothing appears to be as it seems, there are ulterior motives that are working and reworking these Indigenous-Settler relationships. Disguise in this chapter helps the cultural other to infiltrate and advance their agenda. The Indigenous tribes came seemingly “without arms, offensive or defensive of any kind” (219), which allowed them to permeate the fort and bring them closer to execute their plan to depose their British rivals. In this same instance, the Natives learn the true nature of the British and the dangers of their treachery that awaited him and his people. The British use disguise to create the illusion of friendship and trust, when in reality, an impenetrable force was assembled, ready for battle should it arise. A deep-seated fear of the cultural other drives this Indigenous-Settler relationship, disrupting trust in visual cues and prevents peace from being achieved.

Chapter 7

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 8

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 9

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 10

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 11

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Chapter 12

Key Events

Analysis and Themes

Works Cited

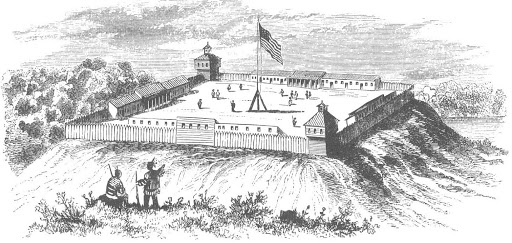

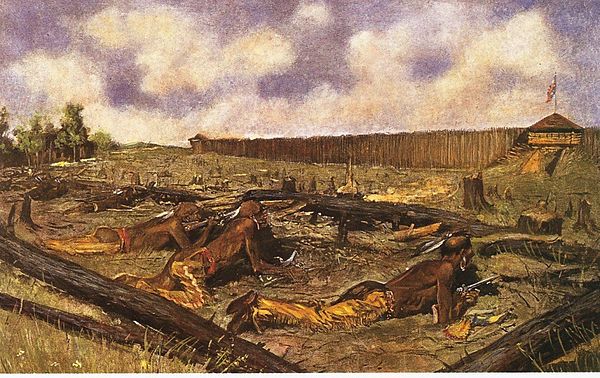

Fort Shelby/Fort Detroit. Military History of the Upper Great Lakes, https://ss.sites.mtu.edu/mhugl/2015/10/11/fort-shelbyfort-detroit/. Accessed 14 June 2020.

McCrea, Harold. Wacousta or, The Prophecy: A Tale of the Canadas. 1987. Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9196092-wacousta-or-the-prophecy. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Remington, Frederic. The Siege of Fort Detroit. 1861-1909. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Detroit. Accessed 14 June 2020.

Richardson, John. Wacousta or, The Prophecy: A Tale of the Canadas. Edited by Douglas Richard Cronk, Carleton University Press, 1987.