Author

From Wikousta

| Revision as of 21:04, 10 June 2020 (edit) Bs18rt (Talk | contribs) (→Group 10 – The Author) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 21:04, 10 June 2020 (edit) (undo) Bs18rt (Talk | contribs) (→Group 10 – The Author) Next diff → |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| Wacoustas author John Richardson was born on October 4th, 1796, in Queenston at Fort George. He was the son of Robert Richardson, a surgeon with the Queen's Rangers, and Madelaine Askin Richardson. His mother, Madelaine, was said to be part Indigenous from the Odawa (Ottawas) tribe. There is not much known about his early life when he was living at Fort George. In 1802, he moved to Sandwich, now Windsor, to live with his maternal grandparents. His grandparents were John and Marie-Archange Askin. Moving on to 1812, Richardson joined the British army as a gentleman volunteer in the 41st regiment. He fought alongside Tecumseh and General Isaac Brock during the War of 1812 and was present at the capture of Détroit. On October 5th, 1813, he was captured during the battle of Moraviantown by American forces and was held prisoner in Kentucky. In 1814 he was released and joined the Kings 8th regiment. The regiment got deployed to Europe in 1815 to fight against Napoleon but arrived shortly after the battle at Waterloo. Later that year, Richardson was promoted to Lieutenant. In February of 1816, Richardson took time off to go live in London on half-pay. Then, in May of the same year, he joined the 2nd regiment as second-Lieutenant. From 1816 to 1818, Richardson served in the West Indies, specifically in Barbados and Grenada. There, he supposedly married a woman but was widowed soon after. In the fall of 1818, Richardson went back on half-pay in London and Paris as part of the 92nd regiment. While he lived in London in 1826, Richardson's literary career began. | Wacoustas author John Richardson was born on October 4th, 1796, in Queenston at Fort George. He was the son of Robert Richardson, a surgeon with the Queen's Rangers, and Madelaine Askin Richardson. His mother, Madelaine, was said to be part Indigenous from the Odawa (Ottawas) tribe. There is not much known about his early life when he was living at Fort George. In 1802, he moved to Sandwich, now Windsor, to live with his maternal grandparents. His grandparents were John and Marie-Archange Askin. Moving on to 1812, Richardson joined the British army as a gentleman volunteer in the 41st regiment. He fought alongside Tecumseh and General Isaac Brock during the War of 1812 and was present at the capture of Détroit. On October 5th, 1813, he was captured during the battle of Moraviantown by American forces and was held prisoner in Kentucky. In 1814 he was released and joined the Kings 8th regiment. The regiment got deployed to Europe in 1815 to fight against Napoleon but arrived shortly after the battle at Waterloo. Later that year, Richardson was promoted to Lieutenant. In February of 1816, Richardson took time off to go live in London on half-pay. Then, in May of the same year, he joined the 2nd regiment as second-Lieutenant. From 1816 to 1818, Richardson served in the West Indies, specifically in Barbados and Grenada. There, he supposedly married a woman but was widowed soon after. In the fall of 1818, Richardson went back on half-pay in London and Paris as part of the 92nd regiment. While he lived in London in 1826, Richardson's literary career began. | ||

| - | <gallery> | ||

| - | Image:Example.jpg|John Richardson | ||

| - | </gallery> | ||

| He published his first series of literary works, ''A Canadian Campaign'' in the ''New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal'' from 1826-1827. His poem ''Tecumseh; or, the warrior of the west'' got published in 1828. He pulled from his experience fighting alongside Tecumseh in the War of 1812 to inspire this poem. Richardson's first novel ''Écarté; or, the Salons of Paris'', was printed in 1829. In 1830, he published two poems titled ''Kensignton Gardens'' In 1830 and ''A Satirical Trifle'' and later that year, he co-wrote ''Frascati's: or, Scenes in Paris'', the sequel to ''Écarté'', with Justin Brenan. Come 1832, Richardson marries his second wife, Maria Caroline Grayson, on April 2nd. ''Wacousta, or, The Prophecy; A Tale of the Canadas'' was issued in the same year in London, England. | He published his first series of literary works, ''A Canadian Campaign'' in the ''New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal'' from 1826-1827. His poem ''Tecumseh; or, the warrior of the west'' got published in 1828. He pulled from his experience fighting alongside Tecumseh in the War of 1812 to inspire this poem. Richardson's first novel ''Écarté; or, the Salons of Paris'', was printed in 1829. In 1830, he published two poems titled ''Kensignton Gardens'' In 1830 and ''A Satirical Trifle'' and later that year, he co-wrote ''Frascati's: or, Scenes in Paris'', the sequel to ''Écarté'', with Justin Brenan. Come 1832, Richardson marries his second wife, Maria Caroline Grayson, on April 2nd. ''Wacousta, or, The Prophecy; A Tale of the Canadas'' was issued in the same year in London, England. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 8: | ||

| After his deployment in Spain, Richardson was hired by The Times of London as a columnist to write in Canada. He and his wife made their way to Canada in 1838. While in Canada, Richardson published the sequel to ''Wacousta'', entitled ''The Canadian brothers; or, the prophecy fulfilled'' in Montreal. He established a printing press in Brockville, where he published some political chronicles from 1841-1842. In 1843 he relocated to Kingston and continued with his work. His chronicles would challenge laws, policies, and authority in Canada. In 1845, Richardson declared bankruptcy and sold his printing press. In May of the same year, the Governor appointed Richardson superintendent of police for the Welland canal; thus, he and his wife moved to St Catharines. In August, his wife passed away. In 1846, he was dismissed as superintendent of police, and he resumed writing political chronicles for newspapers in Montreal. Moving on to 1847, he published ''Eight Years in Canada'' and its sequel ''The guards in Canada; or, the point of honor'' one year later in 1848. Due to financial troubles, Richardson moved to New York in 1849, hoping to find a more captive audience for his writing. For the three following years, he published a few books and wrote short stories for magazines and newspapers such as ''Hardscrabble; or, the fall of Chicago'' (1850) and ''Wau-nan-gee; or, the massacre at Chicago'' (1851). In 1852, John Richardson died on May 12th in New York at the age of 56. His supposed cause of death was erysipelas, also known as St Anthony's fire, which may have been caused by malnourishment. | After his deployment in Spain, Richardson was hired by The Times of London as a columnist to write in Canada. He and his wife made their way to Canada in 1838. While in Canada, Richardson published the sequel to ''Wacousta'', entitled ''The Canadian brothers; or, the prophecy fulfilled'' in Montreal. He established a printing press in Brockville, where he published some political chronicles from 1841-1842. In 1843 he relocated to Kingston and continued with his work. His chronicles would challenge laws, policies, and authority in Canada. In 1845, Richardson declared bankruptcy and sold his printing press. In May of the same year, the Governor appointed Richardson superintendent of police for the Welland canal; thus, he and his wife moved to St Catharines. In August, his wife passed away. In 1846, he was dismissed as superintendent of police, and he resumed writing political chronicles for newspapers in Montreal. Moving on to 1847, he published ''Eight Years in Canada'' and its sequel ''The guards in Canada; or, the point of honor'' one year later in 1848. Due to financial troubles, Richardson moved to New York in 1849, hoping to find a more captive audience for his writing. For the three following years, he published a few books and wrote short stories for magazines and newspapers such as ''Hardscrabble; or, the fall of Chicago'' (1850) and ''Wau-nan-gee; or, the massacre at Chicago'' (1851). In 1852, John Richardson died on May 12th in New York at the age of 56. His supposed cause of death was erysipelas, also known as St Anthony's fire, which may have been caused by malnourishment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | Image:Example.jpg|John Richardson | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| == '''Volume 1''' == | == '''Volume 1''' == | ||

Revision as of 21:04, 10 June 2020

Contents |

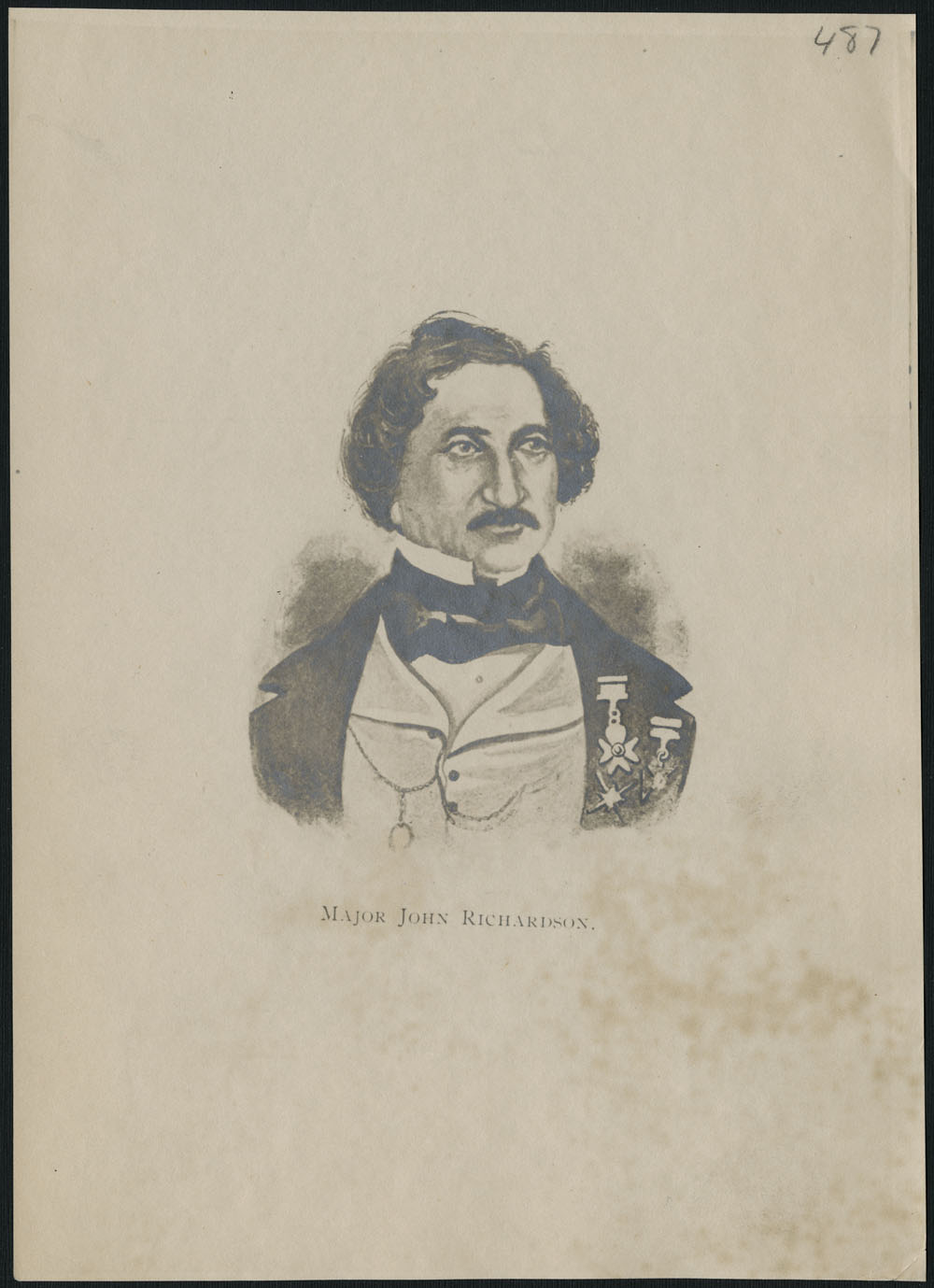

Group 10 – The Author

Wacoustas author John Richardson was born on October 4th, 1796, in Queenston at Fort George. He was the son of Robert Richardson, a surgeon with the Queen's Rangers, and Madelaine Askin Richardson. His mother, Madelaine, was said to be part Indigenous from the Odawa (Ottawas) tribe. There is not much known about his early life when he was living at Fort George. In 1802, he moved to Sandwich, now Windsor, to live with his maternal grandparents. His grandparents were John and Marie-Archange Askin. Moving on to 1812, Richardson joined the British army as a gentleman volunteer in the 41st regiment. He fought alongside Tecumseh and General Isaac Brock during the War of 1812 and was present at the capture of Détroit. On October 5th, 1813, he was captured during the battle of Moraviantown by American forces and was held prisoner in Kentucky. In 1814 he was released and joined the Kings 8th regiment. The regiment got deployed to Europe in 1815 to fight against Napoleon but arrived shortly after the battle at Waterloo. Later that year, Richardson was promoted to Lieutenant. In February of 1816, Richardson took time off to go live in London on half-pay. Then, in May of the same year, he joined the 2nd regiment as second-Lieutenant. From 1816 to 1818, Richardson served in the West Indies, specifically in Barbados and Grenada. There, he supposedly married a woman but was widowed soon after. In the fall of 1818, Richardson went back on half-pay in London and Paris as part of the 92nd regiment. While he lived in London in 1826, Richardson's literary career began.

He published his first series of literary works, A Canadian Campaign in the New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal from 1826-1827. His poem Tecumseh; or, the warrior of the west got published in 1828. He pulled from his experience fighting alongside Tecumseh in the War of 1812 to inspire this poem. Richardson's first novel Écarté; or, the Salons of Paris, was printed in 1829. In 1830, he published two poems titled Kensignton Gardens In 1830 and A Satirical Trifle and later that year, he co-wrote Frascati's: or, Scenes in Paris, the sequel to Écarté, with Justin Brenan. Come 1832, Richardson marries his second wife, Maria Caroline Grayson, on April 2nd. Wacousta, or, The Prophecy; A Tale of the Canadas was issued in the same year in London, England.

Looking forward to 1835, Richardson joined the British auxiliary legion as a Captain and was stationed in Spain during what was the First Carlist War. He published the Journal of the movements of the British Legion in 1836 and the following edition Movements of the British Legion in 1837. Due to the content of these works, Richardson came under fire for criticizing his commander Lieutenant-General George de Lacy Evans and exposing his ineptitudes. His Personal Memoirs, published in 1838 and his satirical novel Jack Brag in Spain, continued to present the incompetence of the British Legion. Richardson was presented to a military court and charged for "discrediting the conduct of the Legion," which was then changed to "cowardice in battle." Having been wounded while in Spain, he was absolved of all charges and subsequently promoted to major. Still residing in Spain, Richardson was knighted in the military order of St Ferdinand.

After his deployment in Spain, Richardson was hired by The Times of London as a columnist to write in Canada. He and his wife made their way to Canada in 1838. While in Canada, Richardson published the sequel to Wacousta, entitled The Canadian brothers; or, the prophecy fulfilled in Montreal. He established a printing press in Brockville, where he published some political chronicles from 1841-1842. In 1843 he relocated to Kingston and continued with his work. His chronicles would challenge laws, policies, and authority in Canada. In 1845, Richardson declared bankruptcy and sold his printing press. In May of the same year, the Governor appointed Richardson superintendent of police for the Welland canal; thus, he and his wife moved to St Catharines. In August, his wife passed away. In 1846, he was dismissed as superintendent of police, and he resumed writing political chronicles for newspapers in Montreal. Moving on to 1847, he published Eight Years in Canada and its sequel The guards in Canada; or, the point of honor one year later in 1848. Due to financial troubles, Richardson moved to New York in 1849, hoping to find a more captive audience for his writing. For the three following years, he published a few books and wrote short stories for magazines and newspapers such as Hardscrabble; or, the fall of Chicago (1850) and Wau-nan-gee; or, the massacre at Chicago (1851). In 1852, John Richardson died on May 12th in New York at the age of 56. His supposed cause of death was erysipelas, also known as St Anthony's fire, which may have been caused by malnourishment.

Volume 1

Throughout Volume One of “Wacousta”, John Richardson sets the foundation upon which the novel explores complex relationships with settler identity and culture. Richardson was born in 1796 as a Canadian with a mix of Scottish and Indigenous heritage (Beasly 1985). With these two backgrounds being vastly different from one another in terms of culture, Richardson would have faced a kind of contact within himself as these two facets of his identity oppose one another. Volume One illustrates Richardson’s love of his home country while also actively making commentary on the influence England had on his beloved nation and its people.

In the opening of the novel, Richardson not only addresses the audience but makes clear the unfamiliarity Europeans collectively possess towards Canada: “As we are about to introduce our readers to scenes with which the European is little familiarised” (9). This is very striking as it implicitly suggests that even now, Europeans do not have a grasp on the land in which they seek to own or the people who rightfully own it. This continues as Richardson describes the chain of lakes that extends “in a north-western direction to the remotest part of these wid regions, which have never yet been pressed by other footsteps than those of the native hunters of the soil” (9). This acknowledgement that Europeans are embarking on literal foreign soil initiates the cue to the reader that the text is a Colonial Travel Narrative along with the characteristics and ideologies that accompany the genre. Richardson continues by detailing the scenery and landscape of the region of Canada the narrative will take place which is primarily Fort Detroit. Richardson was present at the capture of Detroit and his long standing military experience influences the depictions of the British soldiers and life inside the garrison (Beasly 1985).

The Garrison Mentality is evident even in the introduction of the novel through the descriptions of nature: “From this point the St. Lawrence increases in expanse, until, at length, after traversing a country where the traces of civilisation become gradually less and less visible, she finally merges in the gulf, from the centre of which the shores on either hand are often invisible to the naked eye; and in this manner is it imperceptibly lost in that misty ocean, so dangerous to mariners from its deceptive and almost perpetual fogs” (11). The pathetic fallacy of the perpetual fog in connection with the fringes of civilization (i.e. the beginnings of Indigenous territories) symbolize the confusion of the settlers as they navigate a terrain and body of people that are not only foreign but heavily rooted in nature.

The stability of the Europeans in Canada was extremely precarious and this is evident in Richardson’s examination of the military rank system. When discussing their opinions over the depersonal and mechanic nature of promotions in the military system the narrator states: “A moment or two of silence ensued, in the course of which each individual appeared to be bringing home to his own heart the application of the remark just uttered; and which, however they might seek to disguise the truth from themselves, was too forcible to find contradiction from the secret monitor within. And yet of those assembled there was not one, perhaps, who would not, in the hour of glory and of danger, have generously interposed his own frame between that of his companion and the steel or bullet of an enemy. Such are the contradictory elements which compose a soldier’s life” (30). There is a juxtaposition of desire; the desire for security of station and rank that comes with the prestige of being a part of the military while simultaneously rejecting the heartless and unforgiving nature of what being a soldier really means. With England at the time being radically divided by class, there was an immense attraction to join the military as a form of economic security. Richardson in his time as a soldier may have felt these same feelings of conflict as his long military career would have forced him to come to terms with the realities of his position. After Richardson published Wacousta he was discharged for “cowardice in battle” in 1836; after many years of military service the pressures of this lifestyle may have weighed on Richardson and this is evident in his literature (Beasly 1985). This quote outlines just how precarious the station of a soldier really is, in an instant you could lose the life of a close friend and in the next be making the commands; the fragility of ranks symbolize the unstable nature of Britain’s occupation in Canada as their systems of power are not only destructive in and of themselves but also implicitly pit comrades against one another.

The relationship between the British settlers and the Candians is one of tension as they accept gold in “exchange for the necessaries of life” while also experiencing feelings of fear towards them: “As the troops drew nearer, however, they all sank at once into a silence, as much the result of certain unacknowledged and undefined fears, as of the respect the English had ever been accustomed to exact” (119). The diction used in this passage outlines the fear of Canadians towards the British soldiers. Despite the fact that several lines before this passage “the colonist settlers had been cruelly massacred” the fear is not directed towards the Indigenous but to the British. This fear is not questioned but instead is rudimentary in the soldiers' construction of identity as it is not only expected but seen as a form of respect. Richardson’s dual background would have caused him to possibly experience feelings of internal opposition; he states to have an undying love for Canada while simultaneously not denying his devotion to the Crown by joining the British forces. Richardson goes back and forth in his tone surrounding the English and this could be to appease the intended audience of readers while exploring how these ideas can be challenged. By tapping into these feelings of conflict within himself, Richardson is able to construct a picture of the British that fits the mold of colonial literature while also illuminating the unstable and chaotic behavior of the settlers in response to their shifting understandings of identity.

Volume 2

Volume 3

“Wacousta” volume 3 is significant to examine regarding its connection to the author because of many factors including character development, plot development, the use of language, themes, and the tone of volume 3. The focus of this section will be on the genres depicted within the novel and both character and plot development surrounding Wacousta’s true identity as Reginald Morton. The discovery of Wacousta as a white man in the final volume of the text rather than the first or second is important to note because of what it reveals about John Richardson’s motives in the representations of race within the novel.

There are many conflicting genres that are present in the novel. Richardson manages to pack multiple intertwining genres within the text. There are elements of a tragedy novel which can be seen by the death of both major and minor characters and elements of a comedy novel because of the marriage that occurs between Fredrick and Madeline. Although there are many overlapping genres within the novel, Richardson uses many gothic tropes such as the gloomy setting, Ellen Halloway’s curse, brutal violence, and the monstrous character, Wacousta. The intermingling of genres reflects the complex position that Richardson possesses because of his cultural background. John Richardson was from both an Indigenous and Scottish decent making him simultaneously loyal to the crown yet aware of the valuable contributions that the Indigenous community made in the development of Canada. In compiling the book with multiple texts, Richardson gives the novel an unusual tone because of the text’s inability to be categorized into one genre which may be a reflection of his views on Canadian history and how it cannot be told through a singular lens.

Similarly, the discovery of Wacousta’s true identity as a white man named Reginald Morton on page 437 introduces an entirely new area of discussion surrounding race and identity. Wacousta’s identity plays on the themes of deception that can be seen within the novel and forces readers to challenge the stereotypes they may have previously possessed. In a conversation between Clara de Haldimar and Wacousta, both readers and Clara discover that she “has been the wife of two Reginald Mortons” (439). A connection is also drawn to Frank Halloway who shares the same name as Wacousta. It is as though Wacousta is avenging Halloway’s death while simultaneously indulging in his own revenge plot. Wacousta’s hidden identity and his actions prove that binaries are purely imaginary (Lee, 53). Readers must consider the notion of Indigeneity as a performed identity and what Richardson’s goals were in developing a character such as Wacousta.

Wacousta is arguably the most savage character within the novel and RIchardson holds off on revealing to readers that he is a white man to add shock value to the plot and to forces readers to question the preconceived identity of the “white colonizers” as civilized. Through the reveal of Wacousta’s true identity in the third volume, Richardson critiques the way Canadian history has been written. Most of Canadian history has been written through imperial eyes with eurocentric views and has caused the tainting of Indigenous identities and the uplifting of colonial identities. Richardson critiques the notion that Indigenous individuals were the “savages” who needed to be tamed by the “civilized” colonists by making the most monstrous character a white man who is driven by his thirst for revenge. Richardson utilizes Wacousta’s character to prove that the men that a majority of history has painted as “civil” can cause just as much harm and be “savages” themselves. The cultural divide that Richardson experiences with a background in both Indigeneity and Scottish are reflected in his work. Richardson proves that corruption does not discriminate between cultures and tries to challenge the stereotypes surrounding Indigenous peoples.

Volume 3 of Wacousta is packed with parallels that can be drawn to John Richardson’s life but the most notable one is the revealing of Wacousta as a white man simply disguised as an Indigenous person. The blurring of identities is reflective of Richardson’s own personal struggle to grasp both sides of his identity equally. The volume sheds light on the reality that being of a certain race does not automatically place you in a “good” or “bad” group.

Notes and References

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “John Richardson.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 May 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/John-Richardson-Canadian-writer.

Beasly , David R. “Biography – RICHARDSON, JOHN (1796-1852) – Volume VIII (1851-1860) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Home – Dictionary of Canadian Biography, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 1985, www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_john_1796_1852_8E.html.

Richardson, John. Wacousta or, The Prophecy; A Tale of the Canadas. Edited by Douglas Cronk, Carleton University Press Inc., 1987.